German Cannabis: Political Posturing vs. Market Reality

Ben Stevens breaks it down.

Note: Cannabis Confidential shifted content strategy in 2026 with insights from trusted partners, industry insiders, and thought leaders who’ve got something to say. There will be no more paywalls or content fees; think of it as The Players Tribune for the cannabis industry, with an ethos of honesty, trust and respect.

Last week (Nov. 21, 2025), Germany’s Bundesrat held a debate on the hotly contested amendments aimed at significantly restricting medical cannabis prescriptions, and potentially transforming the industry.

The upper house of the German parliament voted to approve some, but not all of the measures, crucially rejecting proposals to ban mail-order prescriptions.

However, during its plenary session, the chamber adopted three core amendments to the Medical Cannabis Act, targeting foreign prescriptions, pricing inconsistencies and advertising practices that have fueled the sector’s explosive growth.

This is far from the end of the road for the bill, which is still subject to change before a final vote next year. While the vote does not give us a definitive answer to how the industry will be regulated moving forward, it does highlight a disconnect between government rhetoric and consumption data.

Health Minister Nina Warken has described the spike in cannabis imports since last April as ‘clear abuse’, yet the recently published annual Epidemiological Survey of Substance Abuse found no statistically significant increase in consumption post-legalization, 12-month prevalence rose from 8.8% in 2021 to 9.8% in 2024, continuing a long-term trend but showing no legalization-driven spike.

Stefan Fritsch, founder and CEO of Grünhorn, argues that effective regulation requires proportionality and evidence. While not opposed to oversight itself, he believes the proposed restrictions lack the medical grounding necessary for sound healthcare policy.

“What many observers outside the industry may not realize is Warken advanced the proposal without first securing internal alignment within her party,” he told BoC.

“If I wanted a bill to pass, the first thing I’d do is consolidate support within my own party, which she didn’t. Instead, she went out alone and said, ‘This is what we’re going to do,’ only for members of her own party to immediately say, ‘No, we’re not.’”

Since that initial rollout, the legislative process has moved into a more substantive phase, with expert hearings and legal scrutiny now shaping parliamentary debate. However, Fritsch remains concerned that the underlying proposals still lack the evidence base necessary to justify their impact on patient access.

Coalition dynamics and cannabis

Following Germany’s February 2025 elections, the formation of a CDU/CSU-SPD coalition initially raised alarms across the cannabis industry. The CDU/CSU had campaigned on repealing CanG entirely, while the SPD remained committed to the reform as one of the previous coalition’s flagship achievements.

However, the final coalition agreement, reached in April 2025, left the Cannabis Act intact, committing only to an ‘open-ended evaluation’ with results expected in 2026.

“In Germany, we have two parties governing together. Historically, the CDU has always watered down its positions for the SPD. In these first 100 days, you can see they haven’t pushed back hard on anything the SPD has wanted, because they’re focused on keeping the coalition intact. I don’t think cannabis is going to be the issue that makes them suddenly draw a line in the sand.”

With numerous votes still needed to bring the bill into law, Fritsch predicts the next stages are likely to be bogged down in politics.

“Cannabis is just one of many issues on the table. Germany spends more on healthcare than any other developed country but still has poor outcomes in some areas, like heart attack mortality. With so many bigger priorities and with this bill being so controversial, I think any progress will be slow.”

The measure must still pass through parliamentary committees and secure a majority vote in the Bundestag, where the SPD has already signaled opposition.

“We’re already seeing the SPD, the coalition party, publicly saying, ‘We’re not doing this,’” Fritsch said.

“On telemedicine, I don’t think they’ll be able to require patients to physically visit a doctor’s office, but they will likely tighten the rules, possibly requiring video consultations rather than just online forms.”

Fritsch’s concern is not with oversight of telemedicine practices, but with blanket prohibitions that would disproportionately restrict access for chronically ill patients, those with mobility limitations, or patients in rural areas where cannabis-prescribing doctors remain scarce.

He argues the issue isn’t regulation itself, it’s whether the measures are proportionate and actually address the problems they claim to solve.

The pharmacy mail-order ban faces particularly steep legal hurdles. As Fritsch points out, pharmacies are currently permitted to ship far more dangerous controlled substances, including fentanyl and opioids.

“It’s legally difficult to justify banning mail-order cannabis when pharmacies are allowed to ship fentanyl and opioids. Cannabis is something people can grow at home with water and light, so forbidding it by mail just doesn’t make logical sense. I think that part will be removed entirely.”

Positive shift ‘not being considered at all’

The stakes for patients are substantial. According to Bloomwell Group’s latest ‘Cannabis Barometer’ survey of 2,500 medical cannabis patients, 41.7% would revert to the illicit market if digital access were blocked.

A separate survey by MedCanOneStop found even higher numbers, with 59.2% of patients indicating they would switch to illicit sources.

Grünhorn’s internal data paints a similar picture. “We actually ran a survey to see how many would do that if teleclinics or online pharmacies were banned, and over 60% said they would.”

According to Fritsch, in reality, the black market in Germany is ‘big, efficient, and not what politicians think it is’.

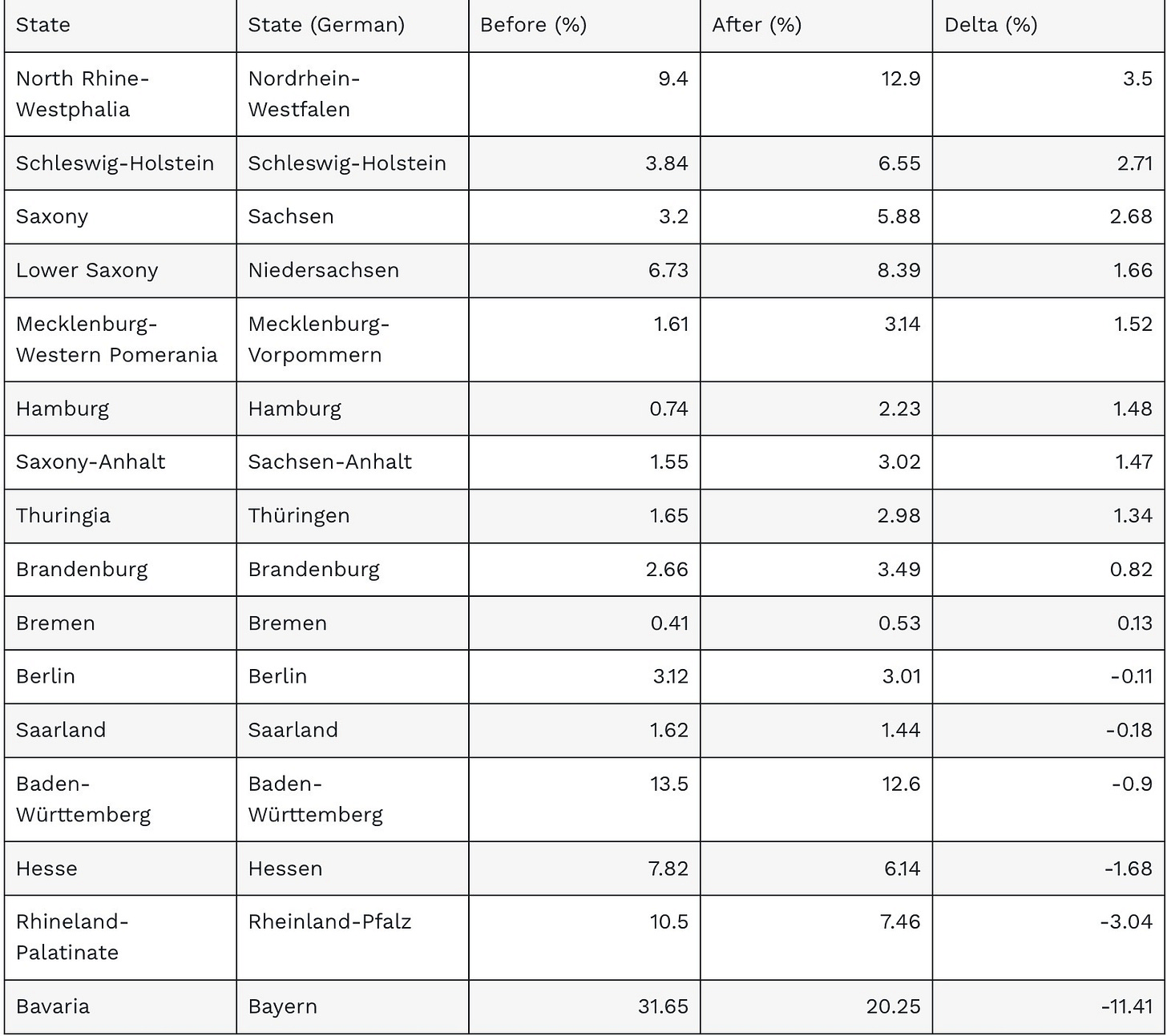

The table below, based on Grünhorn’s data, shows the percentage of patients in each state before and after partial legalization, along with the net change (delta)

“They imagine shady gangsters with guns, but in reality, it’s largely online, delivery-based, and very quick. Many patients still use it today despite legal options, simply because it’s so convenient,”

Pushing patients back toward this system would represent a policy failure far more severe than the current dynamic.

“A patient who was buying from the black market is still a patient. Politicians often say, ‘Look at all these people coming from the black market’, but those are people who have been using cannabis to help with back pain, sleep issues, stress, insomnia, whatever it might be, for a long time. They’ve now moved into a legal, safer channel, with doctors prescribing and pharmacies dispensing.”

“The positive side of that shift is not being considered at all.”

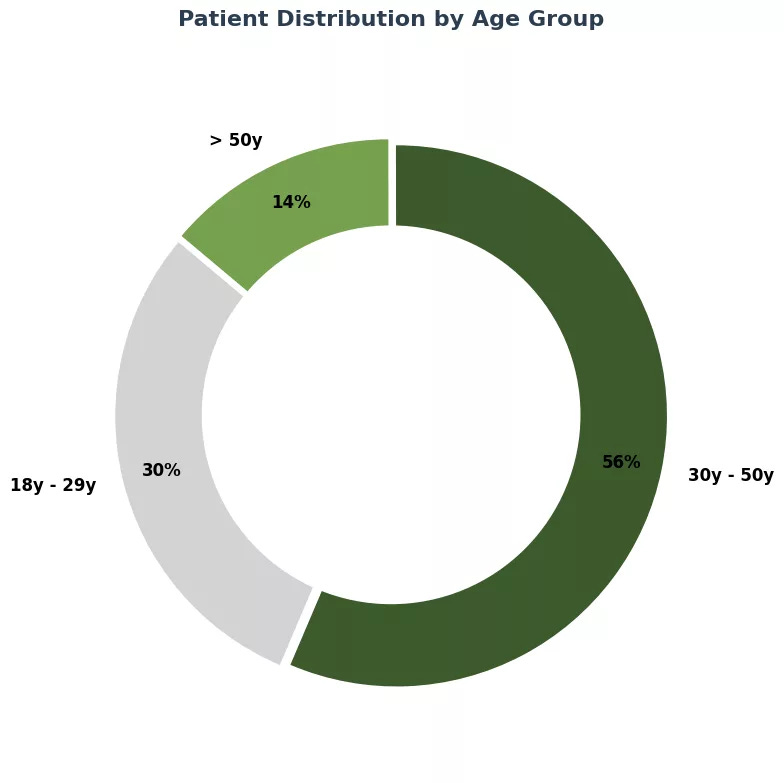

The patient demographic further undermines the government’s framing of medical cannabis users as primarily adult-use consumers operating under the guise of medical treatment. Grünhorn’s data shows the average patient age is 35, a cohort more likely to have families and career responsibilities than to be seeking recreational highs.

“Most people in that age range have kids, careers, and family responsibilities. It’s not really a demographic for recreational abuse,” he continued. “If the average was 25, then sure, maybe we’d have a different conversation. But 35-year-olds aren’t out partying every weekend. That stereotype just doesn’t match the reality.”

The broader concern is that blanket restrictions risk treating all medical cannabis patients under a general suspicion of misuse, a departure from how other controlled prescription medicines are regulated.

Adaptation will overcome panic

Fritsch expects regulatory evolution rather than revolution, and when changes do come, they’re likely to be incremental.

“The government still needs to work through feedback internally and align with the SPD. We’re unlikely to see movement until sometime next year.”

“I expect there will be changes, maybe video consultations instead of online forms, but not a complete reversal. It would be a big mistake to swing all the way back after such a huge change.”

More to the point, recriminalization is wholly impractical, not just politically.

“If they tried to reclassify cannabis as a narcotic, the implications for law enforcement are unimaginable. Local law enforcement and government agencies are legally obliged to track every single milligram of a narcotic, with so many people now growing at home, this would be impossible.

As Germany’s cannabis sector races towards its second year post-CanG, the industry faces a period of uncertainty and adjustment.

Political restrictions remain a possibility, but not an inevitability. Market consolidation appears certain, but what seems abundantly clear is that cannabis in Germany has now crossed the Rubicon.

“Yes, it was a big change, and yes, some parts have gone too far, but that’s normal with a shift of this scale,” Fritsch concluded.

“Now it’s up to the industry to pull back in certain areas and for the government to find a framework it’s comfortable moving forward with.

“The lid’s off, they wont get it back on.”

This is Third-Party content and does not reflect (or not not reflect) the views of Cannabis Confidential or CB1 Capital.